There’s a constant contradiction between governments’ vague handwringing over unemployment numbers and the quiet exclusion of anyone who’s hit 50. In a recent survey, half of HR professionals admitted they’d be reluctant to shortlist anyone over 55.

Of course, it’s not supposed to work like that, but there are plenty of ways to avoid direct accusations. My favourite? “Too experienced for the job.” A backhanded compliment that serves as polite dismissal. You’re out of the running, permanently.

In a recent Telegraph article, Sarah Young described the soul-destroying experience of sending her CV into faceless online space—300 times last year alone. “I’ve worked for years in the fintech industry in both large global corporates and small start-ups, but in spite of applying for over 300 roles through LinkedIn and my networks, I’ve had no joy.

“When you apply for jobs online, you don’t get to speak to anyone, and if your CV doesn’t get through the auto ATS (applicant tracking systems) process, you’re stymied – and I can only assume that age is the huge barrier.” – Sarah Young

Over the years, some remarkable films have captured the quiet crisis facing this age group. From clinical boardroom sackings to the desperate job hunt that follows, and the rare second chance that proves what we all suspect: that, given half a chance, many older people could help reverse the West’s economic decline.

The Corporation: Death by HR Playbook

The French film The Corporation opens with what might be the most terrifying horror scene for a 50-something professional: a roomful of HR execs being trained in the Alps on how to “let go of the Unwanted Ones.”

The lead character is an ambitious young HR professional, coached by her business school mentor to execute the ultimate cost-cutting tactic: easing out older employees, regardless of their contribution. The goal is clear—lower the wage bill by nudging out those who’ve earned higher salaries through decades of experience.

The tactics are chillingly sophisticated. One “sideways move” is offered that’s carefully designed to be logistically impossible for the target without tearing their family life apart. It’s termination by technicality—a corporate execution with no fingerprints.

When one employee responds by jumping from the roof, our HR wunderkind starts to unravel. Her transformation—from dutiful functionary to whistleblower—reveals just how institutionalised ageism has become. These tactics have become so normalised, we barely blink when another 55-year-old “chooses” to pursue “new opportunities”.

Le Couperet (The Axe): Turning the Tables

If The Corporation shows the clinical disposal of careers, Costa-Gavras’s Le Couperet confronts the raw fallout. After two years of unemployment, the protagonist—a chemist played by José Garcia—resorts to drastic measures. He places a fake job advert for his own role and begins eliminating more qualified competitors. Literally.

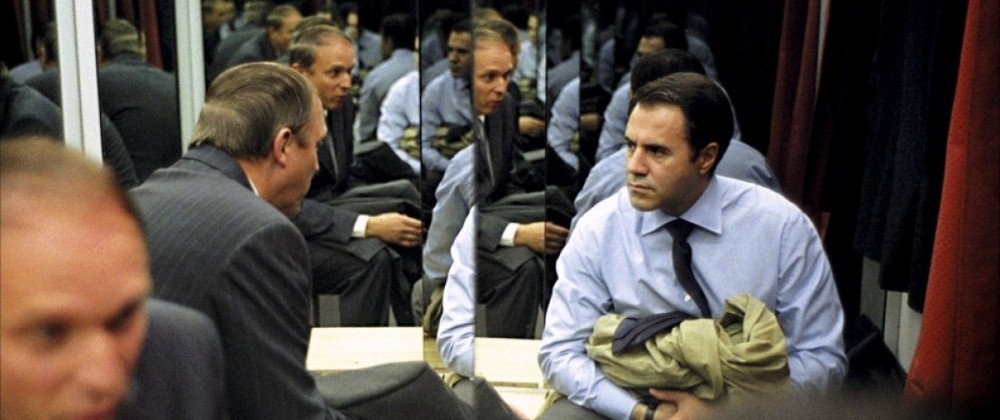

The film’s power lies in its disturbing plausibility. Bruno’s despair is all too familiar: asking ex-colleagues for references with that sharp intake of breath, answering patronising questions from interviewers half his age, or watching someone skim his CV before firing off a line of hostile questioning.

There’s one scene that captures it perfectly: Bruno sits across from a young interviewer who treats him like a relic. The CV is barely glanced at. The whole process is less a job interview, more a performance of dominance. The unspoken power dynamic is clear: one side has the keys to survival, and they know it.

“No job. No money. No life.” Bruno mutters—and it lands like a punch.

The film doesn’t just explore the individual’s crisis. It asks a far larger question: what kind of system creates this level of desperation, and then pretends to be surprised by what it produces?

The Intern: What Could Be

Robert De Niro’s character in The Intern flips the script. A 70-year-old widower joins a buzzing start-up as a “senior intern”—biding his time, observing quietly, and eventually proving his worth.

It’s hopeful, perhaps naively so, but crucial. It shows what’s possible when prejudice is suspended. De Niro’s character brings precisely the qualities his younger colleagues lack: perspective, patience, a refined sense of interpersonal dynamics, and the wisdom to sidestep drama rather than escalate it.

It’s a charming vision. The tragedy is how rarely it reflects reality.

Watch the trailer below:

The Slow Awakening

There are signs—dim but discernible—that things are shifting. As labour markets tighten, some companies are rediscovering the value of experience. Programmes known as “returnships” are emerging, aimed at mid-career professionals. But for the millions currently cast aside, this awakening is far too slow.

Demographics are forcing a rethink. As populations age across the developed world, the economic lunacy of discarding older workers is becoming undeniable. Even the most cold-blooded CEOs are beginning to realise that you can’t simultaneously decry labour shortages and sideline your most experienced staff.

Still, for those trapped in mid-career limbo, the wait is excruciating. The emotional cost—depicted so well in the films above—is being paid in real time, in real homes, by real people.

The Real Cost

These films strip away the HR euphemisms and lay bare the human fallout: the fraying marriages, the hollowed-out self-worth, the slow erosion of identity.

They show that ageism in the workforce isn’t just an individual injustice—it’s a collective failure. Decades of accumulated knowledge and skill are being discarded, not because they’re obsolete, but because they’re deemed too expensive.

More disturbing still is how we’ve come to accept it. We watch 58-year-olds vanish from office life, drain retirement accounts meant for their 80s just to survive their 50s—and call it progress.