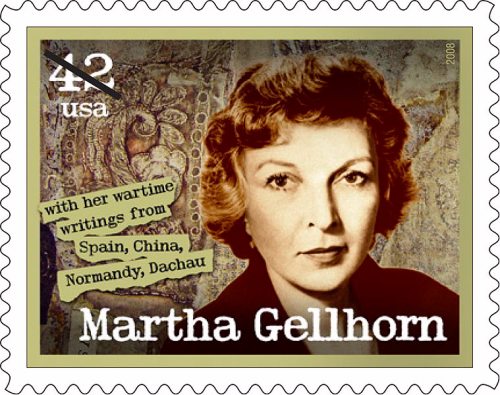

“Writing is payment for the chance to look and learn,” Martha Gellhorn once said, and few journalists have paid such dues or reaped such rewards from the frontlines of history. Some argue she was the finest journalist of the last century, though for decades she laboured under a more famous name that wasn’t her own. Her relationship with Ernest Hemingway would both launch and nearly derail one of the most remarkable careers in war correspondence.

Before she became the woman who snuck onto a hospital ship to cover D-Day, Gellhorn was a 25-year-old with a fierce social conscience, documenting the ravages of the Great Depression in America’s forgotten textile towns. It was this work that caught the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt, beginning a friendship that would profoundly influence both women. The First Lady saw in the young journalist not just talent but a kindred moral clarity that transcended their age difference. In 1936, Gellhorn published “The Trouble I’ve Seen,” her searing account of Depression-era America.

That same fateful year, she met Ernest Hemingway in Key West at Sloppy Joe’s bar. By this point, Hemingway was already a literary giant: his masculine prose style and adventurer persona firmly established in the American imagination. Biographers have noted the immediate spark between them—both were arrestingly attractive, intensely ambitious, and shared a hunger for being where history was happening. When Hemingway suggested they go to Spain to cover the Civil War, it seemed the perfect union of romantic and professional passion.

Spain transformed Gellhorn from a promising young writer into a war correspondent of uncommon insight. It was here she developed what would become her signature approach: intense first-person reporting that refused to hide behind the shield of detachment. The Spanish conflict also cemented her relationship with Hemingway, though Caroline Moorehead, her most thorough biographer, suggests what initially appeared to be mutual admiration contained the seeds of future discord.

“They were too similar in the wrong ways,” Moorehead writes, “both needing to be the center of any story, both requiring endless validation, both believing that experiencing danger was essential to writing truthfully about it.” What worked in Spain—where they were equals in their novelty as war correspondents—would fray dramatically once Hemingway’s fame began to overshadow Gellhorn’s growing reputation.

“I followed the war wherever I could reach it,” Gellhorn would later write. “I had been sent to Europe to do my job, which was not to report the rear areas or the woman’s angle.” This statement captures the essence of both her professional ambition and the gendered expectations she constantly battled—expectations that her relationship with Hemingway simultaneously shielded her from and eventually reinforced.

By the late 1930s, Gellhorn had secured a coveted position with Collier’s Weekly, an American magazine that would become her primary platform during the most consequential decade of the 20th century. Their marriage in 1940 seemed to crown a partnership of equals. But the Second World War would reveal the fundamental asymmetry in how the world perceived them—he was Ernest Hemingway who happened to write war dispatches; she, despite her growing acclaim, was often reduced to being “Hemingway’s wife” who wrote for magazines.

The resentment this created burned slowly at first. Gellhorn covered multiple fronts of the war with distinction, while Hemingway initially remained in Cuba, ostensibly patrolling for German submarines in his fishing boat. Her biographers suggest this period planted the first serious seeds of discontent—Gellhorn believed that a writer’s duty was to be where history was unfolding, and Hemingway’s absence from the European theater struck her as a failure of both professional obligation and courage.

“Ernest begins to rave at me,” she later told her biographer. “My crime is to be at war when he is not… But that is not how he puts it. I am insane. I only want excitement and danger. I have no responsibility to anyone. I am selfish beyond belief.”

The dynamic was deeply ironic. Hemingway had built his entire persona around masculine courage and adventure, yet here was his wife embodying those very qualities while he remained in relative safety. According to several biographers, including Jeffrey Meyers, this role reversal was intolerable to Hemingway’s ego. Gellhorn’s success threatened the carefully constructed image upon which his celebrity partially rested.

After a tense standoff, the couple agreed Hemingway should return to Europe. Unaware she was sealing her own fate, Gellhorn arranged with her contacts for Hemingway to be transported by the RAF. The commander who approved this arrangement was none other than Roald Dahl, then a young officer before his transformation into a literary giant.

What happened next has been described by Gellhorn’s biographers as one of the most revealing episodes in understanding the marriage’s ultimate failure. Of all the publications Hemingway could have approached, he chose Collier’s, which eagerly snapped up the big-name novelist as a correspondent—simultaneously dropping his wife. The magazine’s official explanation was that as a woman, Gellhorn faced military restrictions that Hemingway did not. Each American publication could only have one accredited reporter at certain frontlines, with the result that she was unceremoniously bumped from the roster.

Carl Rollyson, in “Beautiful Exile: The Life of Martha Gellhorn,” suggests this was no coincidence but a deliberate act of professional sabotage. “Hemingway knew exactly what he was doing,” Rollyson writes. “He could have written for any magazine in America, but he chose the one where Martha had found her home. It was a way of putting her in her place.”

Whether calculated or merely self-centered, the impact was devastating. In a single stroke, Gellhorn had lost both her professional platform and any illusion that her marriage existed on equal terms. Her primary identity in the eyes of the world—and now even her own magazine—was as an appendage to Hemingway’s greatness.

What followed reveals her inner strength. Rather than retreat or accept the secondary role assigned to her, Gellhorn became more determined, more inventive, and ultimately more reckless in her pursuit of the story. Initially confined to London rather than the frontlines, she exercised all her journalistic ingenuity to evoke the atmosphere of a war she was forbidden to witness directly. But from her subsequent actions, it’s clear she was plotting something more audacious.

The D-Day invasion would prove the perfect stage for Gellhorn’s most famous act of journalistic defiance—and the final breaking point in her relationship with Hemingway. While he was officially accredited through her former position at Collier’s, Gellhorn engineered her own path to the beaches of Normandy. She managed a spectacular ruse to get aboard a hospital ship without any officials noticing her presence when it set sail for the invasion. When questioned at the port, she claimed to be interviewing nurses. The seemingly innocuous assignment did the trick, and Gellhorn simply walked onto a hospital ship anchored nearby and locked herself in a bathroom until departure.

The symbolism was perfect—Hemingway had taken her official place, so she would create an unofficial one, proving that determination could overcome institutional barriers. While he went through official channels, she literally hid in a bathroom to do what she knew she must. It was both a professional triumph and the death knell for any pretence of marital harmony.

The resulting article appeared in the August 5 issue of Collier’s—the very magazine that had dropped her in favour of her husband. The story makes no mention of her unorthodox reporting methods, focusing instead on the nurses and doctors sailing into danger to collect the wounded from Omaha Beach. According to Moorehead, Gellhorn blended reporting with shipboard duties, helping as an interpreter and finding water and food for wounded soldiers. But always, always observing.

In one poignant scene from her report, she describes a wooden box “looking like a lidless coffin” being lowered to collect a wounded soldier: “The box was raised to our deck, and out of it was lifted a man who was closer to being a child than a man, dead-white and seemingly dying. The first wounded man to be brought to that ship for safety and care was a German prisoner.”

This ability to capture the small, human moments amid historic chaos had become Gellhorn’s signature—a signature distinct from Hemingway’s more self-consciously literary style. While he crafted war into prose that called attention to its own artistry, she seemed to disappear into her subjects, letting them speak through her.

Her apogee in this respect was her report from Dachau. Something that to this day many readers will at some stage stumble across. It is unflinching, angry and strikes the right level of revulsion, never however othering those who had been dehumanised. As she wrote of the survivors: “Furthermore, they were constantly informed by all the camp authorities that they had been abandoned by the world: they were beggars and lucky to receive the daily soup of starvation.” The genius of her reporting lay in how she rehumanized those whom history had tried to render invisible.

Their divorce came in 1945, and though both would continue writing about war, their paths diverged dramatically. Hemingway’s later years were marked by declining health, creative struggles, and eventually suicide. Gellhorn, meanwhile, seemed ambivalent about the split. “I was a writer before I met him, and I was a writer after I left him,” she would later say. “He didn’t help me; he hindered me.”

Closer to the time, however, she was perpetually anxious about whether she was still in his shadow. In a moment of rare self-doubt, she wrote: “Basically what is wrong is that I do not take myself seriously, neither what I am, nor what I believe… A lot of my thinking and acting has been based on showing Ernest. For fear that I reached my highest point, with and through him, and that in every way I am only sinking into obscurity little by little.” This tension—between knowing her own worth and fearing the world would never recognize it—would haunt her for years.

After the divorce, Gellhorn established a life divided between London and a cottage in Wales, creating a rhythm that balanced her continued war reporting with periods of reflective solitude. The Welsh years proved especially fruitful—she wrote daily, developed passionate interests in cooking and gardening, yet remained sharply attuned to the political currents reshaping postwar Britain.

The 1980s miners’ strike particularly galvanized her attention. With the same clarity she had brought to foreign battlefields, Gellhorn recognized the class warfare playing out in the Welsh valleys. “I saw it as a war with two generals,” she observed. “Mrs. Thatcher, ruthless and clever, and Mr. (Arthur) Scargill, a fool.” She cut to the conflict’s essence: “It was exactly like a war: they were fighting for their territory, their community. They said ‘if the mine closes, the village dies’. Mrs. Thatcher had all the money and the power of the state against these people who took home something like £100 a week.”

What distinguishes Gellhorn’s post-Hemingway decades was not just their productivity but their continued evolution. While Hemingway’s final years showed a writer increasingly trapped by his own mythology, eventually silenced by depression and suicide in 1961, Gellhorn’s work gained in precision and moral authority. She covered conflicts in Vietnam, the Middle East, and Central America, each time bringing her characteristic blend of unflinching observation and human empathy to political situations that younger journalists often struggled to parse.

Her later years brought both trauma and wisdom. While in Kenya, she had the horrific experience of running over a child who died. This was something that haunted her for the rest of her life. Yet she maintained a remarkable capacity for joy and engagement with the world. “Why do people talk of the horrors of old age? It’s great,” she declared. “I feel like a fine old car with the parts gradually wearing out, but I’m not complaining,… Those who find growing old terrible are people who haven’t done what they wanted with their lives.”

Even in her ninth decade, Gellhorn maintained a remarkable vitality of mind and spirit. James Fox, in his obituary for The Spectator, recalled receiving a postcard from her at age 86, describing with evident delight her adventures snorkeling around Sinai. Her intellectual powers remained formidable enough for her to submit to a grilling on BBC’s HardTalk in 1997, and to complete a final reporting assignment for the BBC at the remarkable age of 88, offering her perspective on the lasting damage of Thatcherite policies—an analysis informed by nearly a century of witnessing political upheaval.

Biographer Caroline Moorehead suggests that the Hemingway relationship, while painful, ultimately clarified Gellhorn’s artistic path by showing her precisely what she wished to avoid—becoming a writer whose carefully cultivated persona eventually eclipsed their work. Where Hemingway became increasingly mannered and self-referential, Gellhorn moved in the opposite direction, her prose growing more direct, her judgments simultaneously more unsparing yet more compassionate as she aged.

In the end, both she and Hemingway took their own lives, but the symmetry ends there. Hemingway’s suicide at 61 came after years of declining health and creativity; Gellhorn’s at 89 came after a full life and was an act of defiance against cancer and failing eyesight that threatened to take away what she valued most—her independence and her ability to bear witness. She outlived him by 37 years, years filled with work, adventure, and the kind of fierce engagement with the world that had always defined her.

Unlike so many who chronicled the 20th century’s darkest chapters, Gellhorn never retreated into cynicism or detachment. She maintained that essential quality that distinguishes the truly great journalists from the merely competent: the ability to be devastated again and again by human cruelty, yet somehow retain both the will to witness and the gift to make us see.

In a century of war correspondents who perfected the art of appearing unshockable, Martha Gellhorn’s lasting achievement was her refusal to become numb to horror—or to let her readers off the hook by offering them the comfort of emotional distance. Her life reminds us that the greatest journalists don’t simply record history; they force us to confront it with open eyes. And sometimes, when the moment demands it, they lock themselves in bathrooms on hospital ships bound for Normandy, determined to tell the stories that would otherwise go untold.

The ultimate irony may be this: while Hemingway is remembered primarily for his fiction, Gellhorn’s journalism retains a vitality and moral urgency that feels startlingly contemporary. She outlived him by thirty-seven years, outworked him in her final decades, and ultimately outgrew the shadow of being “Hemingway’s wife” to stand as one of the essential witnesses of the twentieth century—on her own uncompromising terms.